Breaking news: working during COVID has been weird.

For folks like yours truly who are holding down an office job, this means a lot of time in the teleconference mines. On one hand, some people (hi) like the five foot commute to the office and the parade of coworkers’ dogs who are definitely good boys and not cursed gremlins like mine. On the other, Zoom, Hangouts, WebEx, and the like have all replaced those blocks of nap-in-the-back-of-the-room time with a gallery view where all your coworkers can see the clutter you’ve got behind you in your apartment and hear the stampede of your children while you’re trying to tack story points onto a Jira ticket.

So there are pros and cons.

Pictured: a gremlin.

I recently started here at Mux in possession of a collection of (metaphorical) hats, and among them is video. Not video tech, not strong opinions about content delivery networks or what options to feed to x264 to get the stream of your dreams, but video: cameras, lenses, microphones, and all the electrical plumbing between them. Here at Mux I’m a Community Engineer on the DevEx team; when you’re all watching Demuxed from October 27-29--because you’re gonna watch, right?--I’ll be running the production from my office here in Boston. And when I was doing the rounds to virtually meet the cast of characters with whom I now work, the same two topics kept coming up.

- Oh, you do video? What should I buy?

- I already bought [all manner of things], why is the quality not everything I dreamed of?

So I asked my boss, one Matt McClure, whether or not I should write something up as an internal wiki page, and even before I got a response over Slack I followed up with something like “wait, that’s silly. To the blog!”. And as much as I’m loath to hand you a shopping list and telling you to hold it for a second, we’re going to break this into a few blog posts. Today we’re going to talk about what to consider when buying a microphone. Next time we’ll talk about how to use it--and how best to use the stuff you might’ve already purchased and are having some trouble with. After that we’ll get into video, with budget options (if any are actually back in stock) and higher-end options alike,

Of course, we’re not alone in writing about this. There’s plenty of great content out there on YouTube, but it can be hard to divine the good stuff from the affiliate-link stuff. And so, as somebody who’s made most of the interesting and some of the expensive mistakes in this space, I figure that we can make answering those questions through the lens of your new Zoom existence--and maybe a little YouTube or podcasting if you’re so inclined--worth your time. We’ll talk a little bit about the history of this stuff and why I recommend the stuff I recommend, and we’ll go from there.

More gremlins may occasionally be involved.

Pictured: bonus gremlins.

Now--“Audio?” I can already hear said by some particularly critical permutation of my audience. “But these are video calls.”

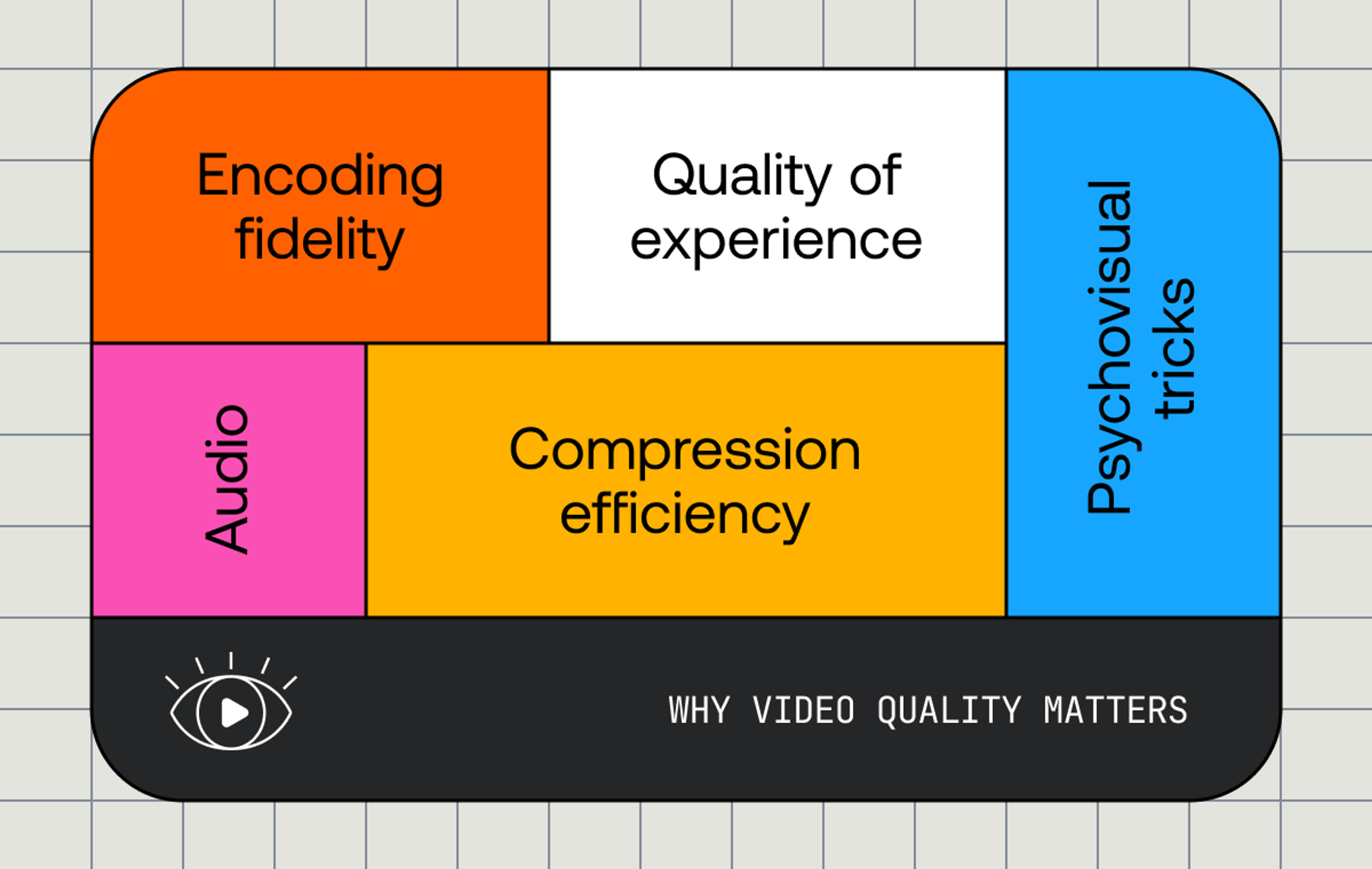

And that’s true. There is, in point of fact, a video component to a video call. But there’s a call component, too, and that’s what everybody is really there to interact with. You see this in content creation circles all the time: you can get away with relatively shabby video and people will still engage with your video or your stream or whatever, but if your audio is a mess of warbling and echoes, people will peace out. Your coworkers are a little more obligated to listen to the interesting kinds of electromagnetic radiation coming out of your computer, but you should be nice to them. And so we’re starting with audio.

Now--we’re gonna talk about spending your money in a second, but I’m a fan of history and I like to meander more than I like to just-the-facts at you, so let’s talk microphones and let’s talk about the whats and whys.

What's a microphone?

Let’s go way, way back to where, in the beginning--we’re talking about the 19th century--we had the carbon microphone. These are loud, grainy, noisy microphones, but they’re nearly indestructible and they work on very low voltages. Since carbon microphones began in the days when amplifier technology was as big as a house and had a habit of electrocuting curious people who touched it, not needing to put too much juice down the wire was considered a Good Thing. Carbon mics are out of the market now but are a cool historical artifact and they stuck around a long time in a number of applications; the one you’re most likely to be familiar with is in telephones, where they continued to be in use up to the 1980s.

You aren’t going to be buying a carbon microphone; the state of the art has moved on. I mention them not just for completeness but because they’re a nice way to illustrate something important: there are factors to consider beyond just “audio quality” and even today we make a lot of trade-offs. A carbon microphone might sound terrible but it’s cheap and electrically simple and it’ll survive slamming a phone down on a carriage a few thousand times. Turns out, sometimes that matters more! In a similar vein, teleconferences aren’t studio recordings, and we want to consider what’s best for that job.

So--what’s out there?

Condensers

Common today are condenser microphones. A condenser is effectively a capacitor, as they’re two metal plates kept close together: a thin diaphragm against which sound waves hit and a more solid backplate. You might hear some old and/or British folks call them capacitor microphones because of it, though the American term seems to have mostly taken hold.

Because that diaphragm plate in a condenser is really thin and light (these days they’re usually something like gold-sputtered mylar), you get a really clear and well-defined signal; the “take” off of that microphone is, relative to the size of the microphone capsule (bigger, to a point, is often better). And that can be great! In the right room, that’ll sound amazing, and it’s why studio mics are very often condensers. But a capsule that’s really good at picking up subtle sound waves is also going to pick up the sound waves of your voice reflecting off of the walls or off of the LCD panel in front of you or the dog/roommate/roommate-dog whose nails are clicking on the floor on the other side of the house. They’re tricky to handle. The streamer-popular Blue Yeti and Blue Snowball are condenser microphones and, by now hopefully not surprisingly, I’m not recommending you buy one. More on that in a tick.

Electret microphones are a subcategory of condensers where the capsule is permanently charged. This lets you make a sensitive microphone in a really small body. Lapel mics tend to be electrets, as do consumer-electronics mics: phone mics, laptop mics, and headset mics all tend to be electrets. It’s totally possible to make a good electret; in the price ranges anybody reading this is interested in, it probably isn’t happening.

Shotgun microphones, or line microphones, are another subcategory of condensers, either standard or electret (and a lot of cheap shotgun microphones are actually just directional electret capsules). They tend to be long and ported along the sides of the microphone and they're intended to have a strong forward response while rejecting noise from the sides and back. Typically you see them hanging from a boom pole, just out of shot during an interview or a bit of dialogue during a movie. If you can afford one, they can be great for teleconferences, narration, and the like--but that probably means this guide isn't for you!

Condensers: super sensitive microphones, for good or for ill. For our use case, usually ill. Or expensive.

Dynamics

Dynamic microphones are built around a moving coil that’s wrapped about a magnet. Sound waves hit the diaphragm attached to the coil, the coil moves, the movement of the coil induces a change in signal voltage thanks to the powerful magnet inside it. And here’s a neat trick: because dynamics work off of the moving-coil principle, they’re also loudspeakers. The reverse is true, too. If you plug a set of headphones into a mic jack and yell into the ear cup really loudly, you will get a (very, very bad) audio signal. This is all just electricity, after all.

Three different dynamic microphones, three different capsules. I can’t show you the guts of a condenser without a hacksaw, though.

Dynamic microphones have one big plus: they can be made to be nearly indestructible. I’ve dropped one of my handheld mics down four flights of steel stairs and the mic didn’t care. This comes at a cost, though. The diaphragm of a dynamic microphone is more rigid, so high-pitched sounds aren’t caught as clearly (or at all) and the sound quality coming off the microphone is distinct--some people call it “worse”, others call it “warmer”. Also, the signal voltage from that moving coil is really small. You need to amplify the signal coming off a dynamic microphone a lot to get something usable.

These characteristics can be minuses. Of course, we’re talking about talking, in an environment where we don’t want a lot of room noise and we might be around a lot of electronics that have a habit of making high-pitched noises off of their power supplies. These characteristics are now awesome, and the sample clips below (recorded without any fancy tricks, so beware, it's intended to be raw) hopefully illustrate that effectively.

Dynamics: nearly optimal spoken-word microphones for the average user.

Ribbons

Ribbon microphones also...exist. They’re an interesting relative (sorta) of dynamic microphones, using a thin ribbon that moves within, rather than around, a static magnet. They have a really specific audio texture, they're really fragile and have to be handled with care, and today they're better suited to studio musicians and folks who really want to sound like Frank Sinatra. They're not suitable for a Zoom call or most other spoken-word stuff.

Ribbons: karaoke is Friday night, not during standup.

So What To Buy?

Congratulations, you are now that mythical creature: an educated consumer. So let’s run down what we want.

- Good noise rejection. This means a dynamic microphone. (You could also go with noise rejection software, like nVidia’s RTX Voice, but I’m assuming most folks aren’t running RTX cards in their work laptops. Just a hunch.)

- Connecting over USB. We don’t want to fall down the XLR-and-audio-interface hole. I mean, I fell down it years ago. But I’m That Guy. You need not be. USB is fine.

- Easy to use. Many microphones are pretty hard to use successfully and your audio can be a bunch of messy plosives (popping sounds off of p and b syllables). We’re going to prioritize making you sound good.

- Reasonably cheap. Let’s try to stay under a hundred bucks USD. Going below about $60 is hard, for reasons we’ll discuss in a minute.

Fortunately, there are a few microphones that fall in this category. There aren’t a ton, but I’ve always found at least one of them in stock and any of the following will do you just fine. (These mics go out of stock fast, so you might need to shop around.)

- Samson Q2U. My go-to, off-the-cuff “what microphone do I need?” recommendation. Obviously a cheaper iteration of the next two, but hey, that’s great!

- Audio Technica AT2005USB. Great, simple, straightforward microphone with pretty similar characteristics as the Q2U, but it's usually a little more expensive. (I like the angled basket more than the spherical one. It has no impact on audio quality.)

- Audio Technica ATR2100x-USB. This and the previous microphone are pretty much the same, but this one has a rounded basket and a USB-C port for maximum bloggability.

The only other microphone that I know of and would recommend in this space is the Rode Podcaster. It’s also about triple the cost of the other three microphones. It’s a really good microphone (I have its non-USB brother, the Rode Procaster), but I wouldn’t buy one unless I had a great reason to.

One important thing to realize: all of these microphones are actually USB sound cards as well. You should be using headphones and you should be plugging them into the microphone. They’ll all give you a near-instant replay of your voice in your own headphones, which will help you know if you’re too close, too far away, that sort of thing. We'll get into that more next week.

What Not To Buy?

- USB condensers. Lots of people recommend Blue’s USB microphones, specifically the Blue Yeti, the Blue Yeti Nano, and the Blue Snowball. I can't follow suit. The Yeti is a fine microphone (the Snowball less so) but you’re paying for a lot of features in that Yeti that you aren’t going to use and you’re getting a pretty sensitive condenser that, in an untreated room, is going to give you much worse audio quality than you’ll expect out of a $130 product; similar problems exist with Yeti competitors like the Razer Seiren or the HyperX Quadcast. They're not bad microphones, but they're not great for this purpose.

- Any USB microphone under $60, sales not included. As with most electronics, you can find a ton of cheap and passable-looking USB microphones on Amazon, all looking near-identical save for the brand name. To the best of my knowledge, these are all cheap condensers (acoustically noisy) with bad electronics (electrically noisy). While you might luck into getting something that only sounds poor because of the room and not because the microphone is picking up a talk-radio station down the street, I wouldn’t spend the time or effort.

Higher-End Buys?

Some folks, and I say this with love because I am one, will look at the above list and go “yeah, okay, but what would I buy if I never want to think about this again?

And that’s a question I can’t really answer in a general way. The above microphones are all totally fine, and in some configurations and with some voices even good. If you want to get into the quality microphone space you’re looking at microphones that are really personal and depend a lot on your voice and just how much money you want to spend. My colleague Phil has a Shure SM7b, which is a $400 microphone with a pretty flat broadcast response that also requires a $100+ audio interface and a $70+ preamplifier for its preamplifier to take a good signal. I typically use a $300 Beyerdynamic M201 TG--a drum microphone!--that, when I stick a silly-huge windscreen on it, makes me sound great. I think. So in addition to that $100+ on an interface and $70+ on a preamp, the windscreen by itself was $35.

It all just adds up.

You’re going to want to hear how microphones sound with different voices to decide what works for you. There are plenty of samples and reviews over on YouTube. Be warned, though. This is a deep, deep cave and it’s easy to end up getting lost. And once you buy one microphone, you're going to buy more. I bought a new microphone this week just to see how it sounds. My girlfriend is making fun of me right now as I type this. Life is a struggle.

We just moved to a new house and this is the pile of microphones I found within arm's reach. In my defense, I bought most of them used. Most of them.

A Thing To Hold Your New Microphone

Your Samson Q2U might look like a handheld microphone, but you’ll probably feel silly holding it for the length of your meeting like you’re hosting Family Double Dare. You need something to hold that microphone in place.

This is a much easier topic than the last and, perhaps surprisingly, I am not a font of knowledge about the popular history of holding things in front of your face. So let’s break it down: you’ve got microphone arms and you’ve got floor stands.

A microphone arm is exactly what they sound like. It’s a simple sheet metal arm with either a clip to grip the edge of your table or desk, or a grommet to drill into the desk. Either way, you’re susceptible to desk vibrations from your keyboard, from a drink on the table, that sort of thing, but in my experience the greater mass of the desk grommets shipped with consumer-grade arms tends to be a little better. We’re probably gonna have to go to Amazon for this one, as my go-to recommendation is the Neewer Upgraded Arm (or the Samson MBA28/MBA38 but they’re out of stock right now) or, for a budget pick, Neewer’s budget arm. There are a lot of similar budget arms; I’ve gotten burned by the more random vendors sometimes and can vouch for Neewer’s being, if not good, at least consistently mediocre--and they’re reliable enough to be pressed into service for other stuff, too. A Neewer budget arm is holding up my 1kg camera-and-mount right now. You don’t need to drop a hundred bucks on a Blue Compass or a Rode PSA-1, though; those are for recording environments, and these days I use Samson MBA28’s instead anyway.

The real power move here, though, is not a mic arm. It is a floor stand. It’s free-standing, so there’s no keyboard noise--you can get this by clipping a mic arm to another table or to the wall with a Heil WM-1, but both of those can be ergonomically troublesome. If you have room for a floor stand with boom arm (often called a Euro boom or Euro stand), I recommend it. It’s easier to get the mic where you want it, there’s less of the boom in frame, and you can either set it up for an overhead mic (for some mics, like the Podcaster) or down low (like the ones listed above). I have used the same On-Stage MS7701B for ten years and there are two more sitting in my garage right now. To me and for thirty bucks, it’s the obvious call, if you’ve got the space.

Next Time

Decent audio is, for my money, the number one way to make Zoom, Hangouts, etc. calls more pleasant for everybody who’s listening to you. (Aside from having something interesting or witty to say, anyway, and that’s your problem.) So hopefully you’ve found something enlightening in here and maybe found for yourself a solid upgrade that’ll clean things up for you on that front.

Next time out will be a shorter one as we’ll talk about how to actually use that microphone to its utmost and, if you’ve already bought something closer to the naughty list, how to get the best out of it that you can. After that, it’s onto video. So keep an eye on the Mux blog for more!